The essay before you has been translated from my book Modiin Talush Me’Ha’Karka (Groundless Intelligence – Success and Failure in the IDF’s Geographic Military Intelligence) [1] which discusses the research division of the IDF’s intelligence branch and the role played by the geographical research segment and the evaluation of the state of a nation. A portion of the original appendices has been revised, and I have even added additional appendices. Following the summary, I have added an Epilogue, which does not appear in the book and is intended to expand on readers’ understanding of the crossing using materials unavailable to me at the time the book was published.

For as long as I can remember, at least from 1962, Israeli intelligence concerned itself with the Suez Canal as a water obstacle. Probably even before I arrived on the scene the subject had received considerable attention, especially after Operation "Rotem,"[1] when Israel was caught by surprise after a significant Egyptian armor force crossed the canal, trundled across the Sinai desert, and deployed on Israel's borders.

Historical background

The Suez Canal, the link between the Mediterranean and Red Sea, was dug in 1859 by a French company under the management of Ferdinand de Lesseps. The canal's purpose was to serve as a waterway between Africa and Europe and the Far East that would shorten the length of sea passage by eliminating the need to circumnavigate Africa. The canal's northern point is at Port Said on the Mediterranean and its southern point is the city of Suez at the northern tip of the Gulf of Suez. Part of its route passes through ancient channels of the Nile that the Egyptians excavated thousands of years ago. The canal is 162 kilometers (about 100 miles) long. In its journey to the sea it traverses three lakes that had been in the area long before the digging of the canal. The excavated sections of canal are only 112 kilometers (about 70 miles) in length. Its width was originally 45 meters, and plans for expansion envisioned the western bank only. Thus, more resources were invested in developing the western bank than the eastern one.

The canal's structure and the technical problems in a crossing

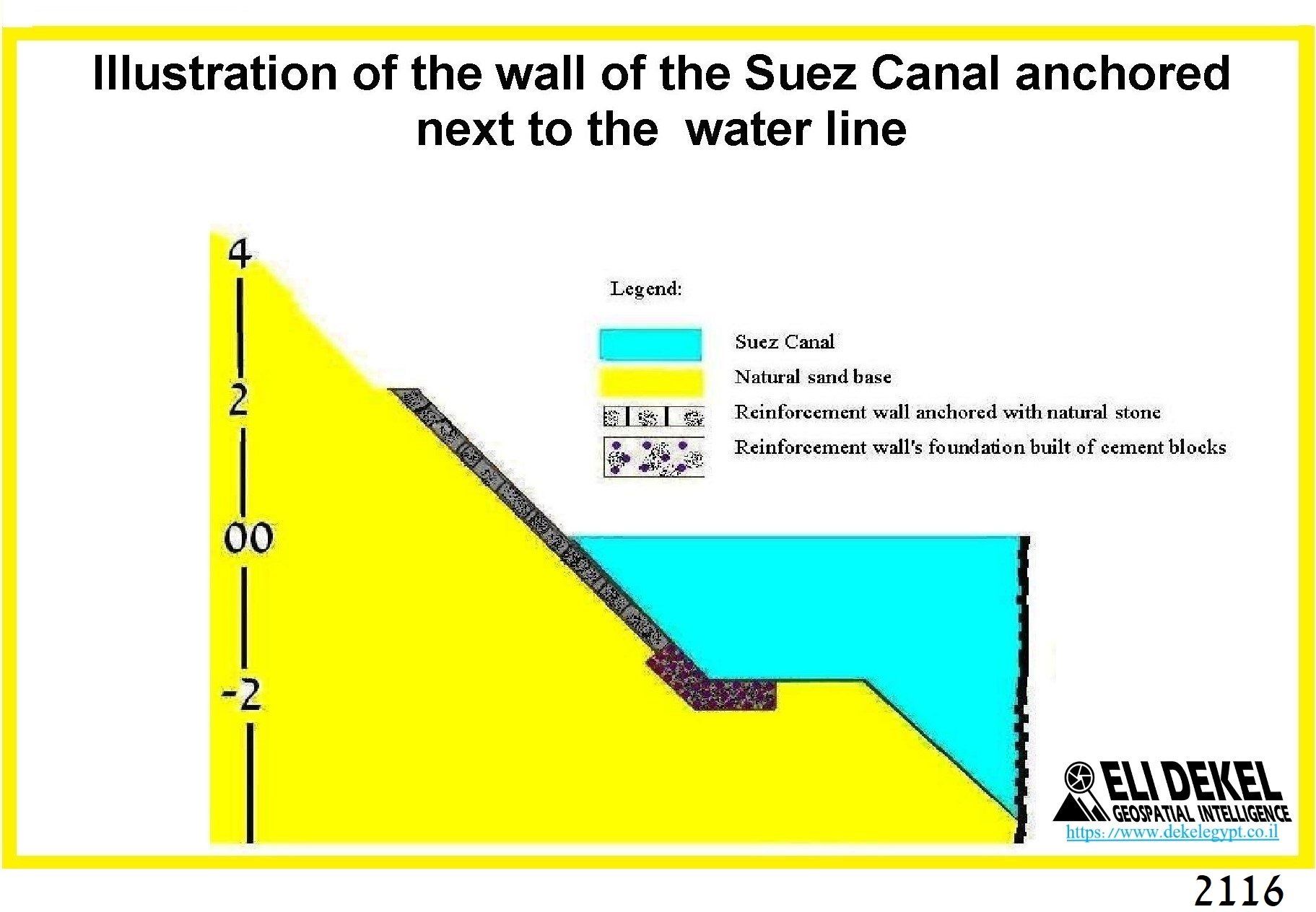

At the time of the Yom Kippur War the canal was 160-180 meters wide. It flowed through a sandy area that demanded constant cleaning of the alluvium that accumulated in its channel. The alluvial deposits originated from dust storms and sand blown in from desert, as well as from the erosion of the banks caused by the propeller movement of ships passing through the waterway. To limit the erosion, the Egyptians laid a rock foundation, essentially 'L'-shaped cement cubes, at a depth of two meters under the water, and above the water they built a one and a half meter stone wall, and above that a retaining wall sloped at a 30-45 degree angle. The cement cubes and incline of the retaining wall proved an obstacle in the construction of floating bridges and use of other amphibious equipment for a canal crossing.

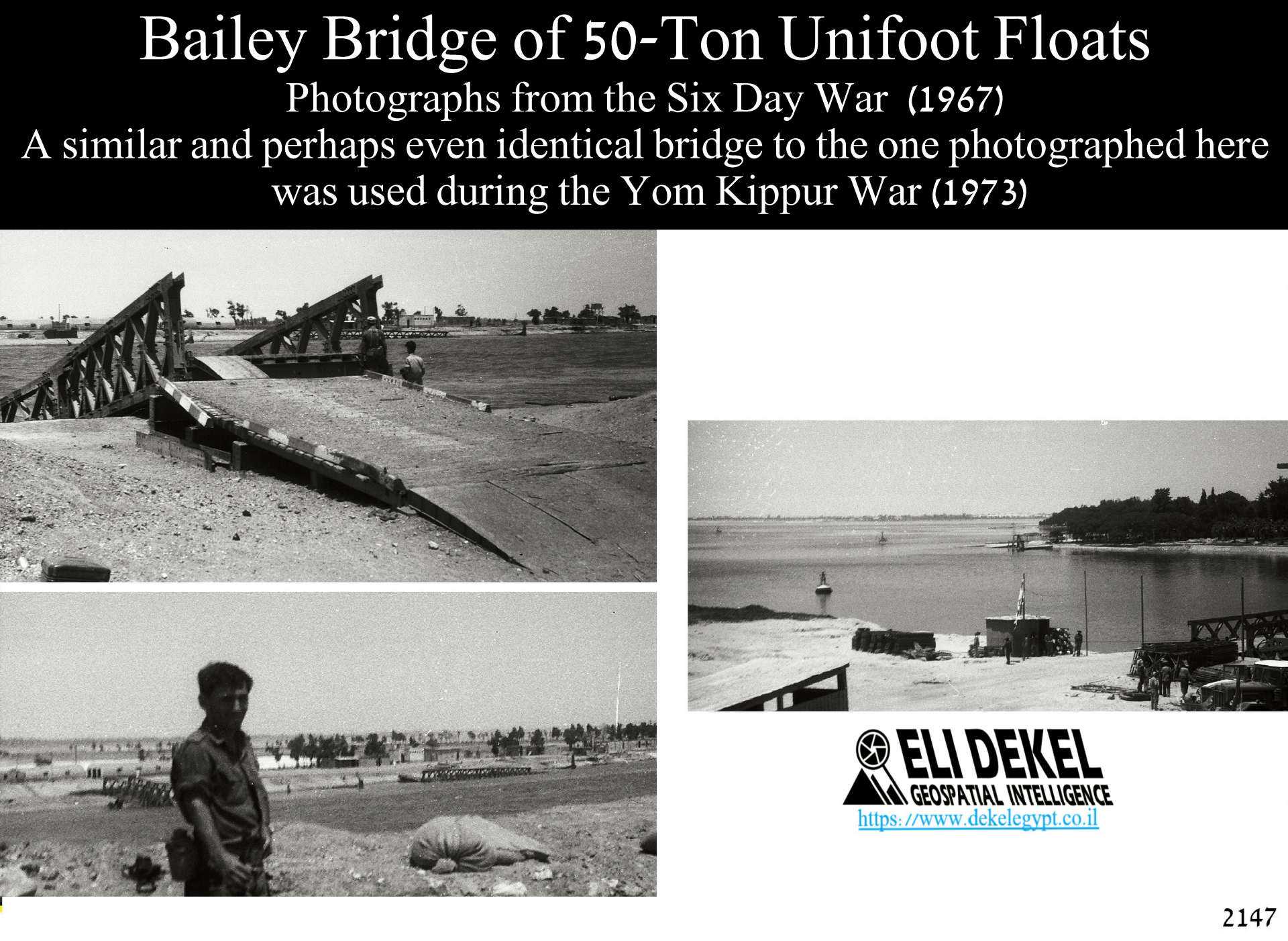

Before the Six-Day War, people and vehicles crossed the canal on civilian ferries and military pontoons. The ferries and military bridges had special jetties built alongside them that functioned as retaining walls on the banks. Different types of bridge were left partially unassembled and anchored on the banks. When a military force had to ford the waterway, commercial sailing was halted, and a bridge assembled. The jetties that built prior to 1967 for the ferries and floating bridges were left intact during the fighting and remained in the area undamaged. Six years later, in the Yom Kippur War, they served the Egyptians in crossing the canal. The following are the seven original crossing areas, listed from north to

south:

A. Port Said (2 kilometers) – two passenger and vehicle ferries; plus pontoon (floating bridge).

B. Kantara (45 kilometers) – two ferries serving the city's population on both sides of the canal.

Kantara was the western-most point on the northern

axis in Sinai from the direction of El Arish

(northwestern Sinai).

C. Firdan (68 kilometers) – located on the Haifa-el Arish-Kantara-Cairo railway line, had a rotating bridge (revolving on its axis) - the only permanent bridge on the canal. The bridge was blown up in the Six-Day War and since then was out of commission.

D. Ismailia (76 kilometers) – passenger and vehicular ferries, pontoon jetties. A bridge spanned the canal not far from Ismailia near Shablia Island in Lake Timsah (Crocodile Lake). Ismailia was the western-most point on the central axis in Sinai from the direction of Refidim (central Sinai).

E. Deversoir (92 kilometers) – jetties for a floating bridge and standing bridge in the northern part of the Great Bitter Lake. This was the IDF's crossing point in the Yom Kippur War.

F. Genifa (133 kilometers) – three jetties for pontoons and one pontoon anchored nearby. The Egyptians crossed the Genifa Bridge in their movement to the Gidi axis.

G. Kubri (157 kilometers) – a ferry and jetties for floating bridges; the Egyptians crossed at Kubri in their movement to the Mitle axis and South Sinai.

Thus, the Egyptians had invaluable experience in crossing the Suez Canal with assault equipment. As stated, in Operation "Rotem" in 1960 they quickly moved armored forces across the waterway and succeeded in surprising us.

Egyptian Bridge demonstration from the 1967 War

After the Six-Day War the Egyptian army deployed five infantry division on the western bank, opposite their respective crossing sectors. These were (in north to south order): the Eighteenth Infantry Division opposite the Kantara crossing sector; the Second Infantry Division opposite Ismailia; the Sixteenth Infantry Division opposite Deversoir; the Seventh Infantry Division opposite Genifa; and the Nineteenth Infantry Division opposite Kubri. To the rear of the frontline divisions, two mechanized and two armored divisions were deployed. All totaled: approximately 2200 tanks and 2000 artillery pieces amassed along the Suez Canal.

Construction of the "Bar-Lev Line" obstacle

During the War of Attrition, not long after the Arab in the Six-Day War, the Egyptians began disrupting and sniping at our forces' movement on the eastern bank. In response, the IDF commenced construction of a defensive layout that included, inter alia, fortifications and a dirt embankment along the canal shore. This embankment and the strongholds went through several stages of development, but in the end a sand wall 15-20 meters high – the "Bar-Lev Line" – created an impassible obstacle for a canal crossing unless heavy engineering equipment was used to break through. Thus, on the eastern bank there rose a "monstrous" obstacle - the elevated sand wall and well-protected strongholds - while on the western bank the Egyptians settled for simpler fortifications made of modular iron hoops. Some of these fortifications were built on the embankment of the sweet water canal. The excavation of this canal, and especially the removal sediment deposits, created a two-to-three meter high dirt wall. In different sections of the sweet water canal and especially in the south – where it lies furthest from the Suez Canal – the Egyptians erected an embankment with strongholds integrated in it. The three meter high dirt wall was not continuous.

Israeli intelligence gathering on the Egyptian infrastructure

After the Six-Day War and outbreak of the War of Attrition, IDF deployment on the canal bank led to an increase in staff and tasks assigned to Section 1's Egyptian subsection. At its peak the subsection numbered eighteen staff members, three with the rank of major. The section head was Major Haim Corman, and his assistant Major Avraham Tal. Given the large number of tasks, work was divided into three teams, each of which operated as an independent subsection. The in-depth infrastructure; the frontline team, headed by the late Benny Kain, dealt with the field armies deployed on the western bank; and the operations team, headed by Major Dov Adler, translated the incoming intelligence data into two groups: one for operational intelligence (raids carried out by Sayeret Matkal - an elite commando unit) and the other for air strikes.

The overall subject of the Suez Canal was handled by Benny Kain, who served during part of the period as a career officer and later as a reservist and part-time civilian worker. Benny can be called "Mr. Canal Crossing." He was the first officer in the intelligence branch to discover that the Egyptians were planning and preparing a canal crossing, and the first to begin tracking their progress methodically and rigorously. My own part in the research on the crossing concentrated on Egyptian preparations being made in the rear. At one point I even served as the acting head of the Egyptian subsection and in this capacity was responsible for the subject. But the belief (that most of the intelligence corps disavowed) that the Egyptians were planning a massive canal crossing and that it was only a question of time, motivated all of us in the subsection, and me at its head, to examine our particular fields for signs of war that were rapidly growing and to plan accordingly. It may be said that the Egyptian subsection was Section 1's leading subsection in the field of Egyptian war planning.

The five discoveries about Egypt's plans for a canal crossing

The first discovery: the Egyptians begin ground preparations

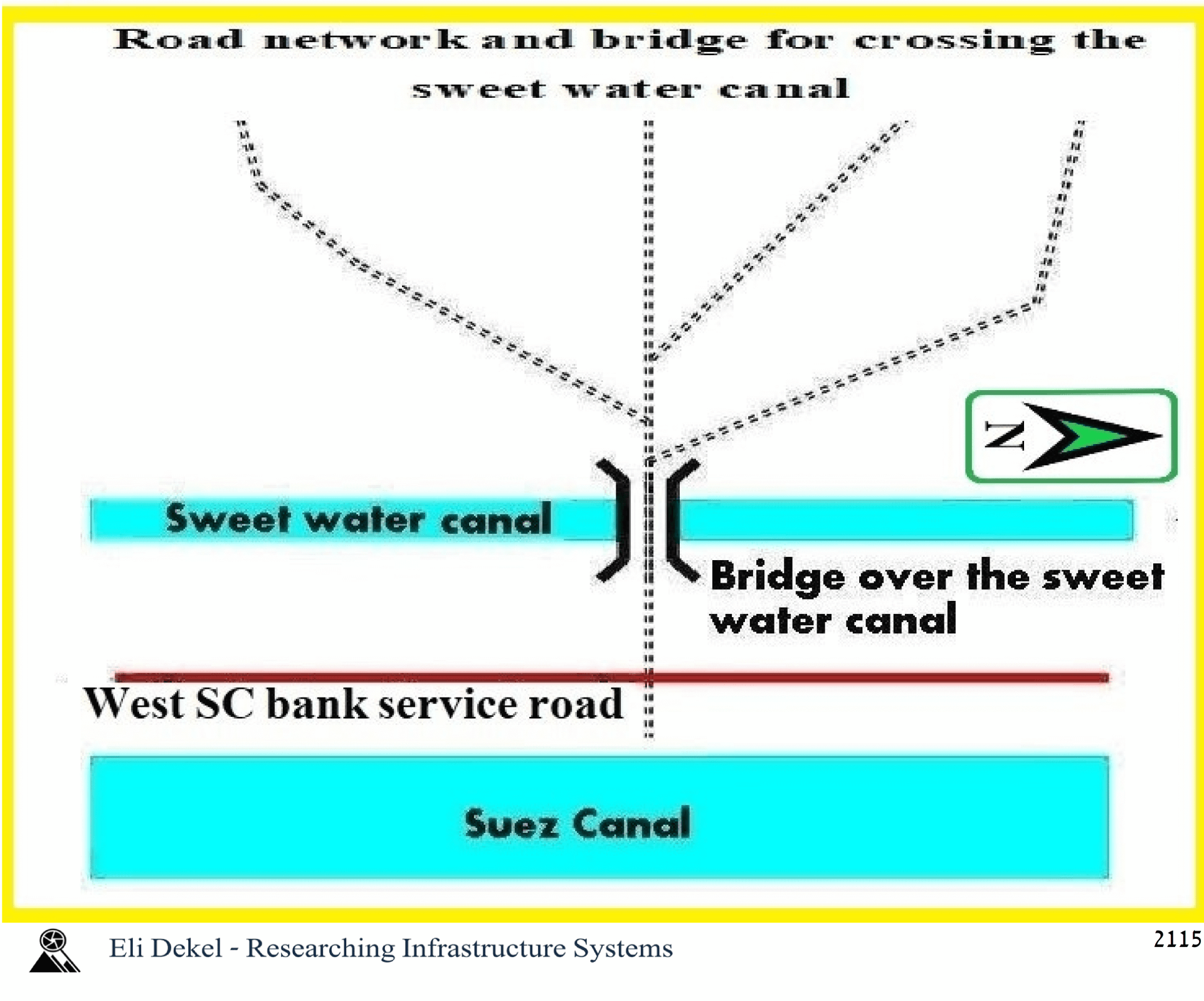

In 1968, just one year after the Egyptian defeat, Benny Kain already discovered a network of dirt roads being paved in the Deversoir[2] area that converged into a single road close to the sweet water canal. The road led to the banks of the sweet water canal where a new bridge was under construction, from where a dirt road was being laid right up to the bank of the Suez Canal.

Benny concluded that the roadworks and the new bridge being built meant that a battalion- or even brigade-sized crossing was in the offing. If it were a smaller force, for a raid or intelligence gathering for example, Benny reasoned, then the Egyptians would not be going to all the trouble of building this infrastructure, since a network of roads and bridges already existed at the sweet water canal and was in no need of expansion.

Benny's discovery, that was studied and confirmed by the section head, Lieutenant Colonel Zalman Gendler ("Jimka"), was put in writing in an intelligence report and caused quite a stir in the intelligence establishment, given the significance of the finding: An army that had recently been trounced and that we thought would require years to recover, manages in less than a year to embark upon preparations for crossing the canal in significant force. Southern Command's intelligence layout and the military subsection in the Egyptian section of the research department rejected Benny's claim and even turned to personal accusations - alleging that he had lost his mind!

They did not even trouble themselves to use the collection layout to refute the claim. The head of the Egyptian subsection, Major Haim Corman, and head of Section 1, "Jimka," dismissed the charges and gave full backing to Benny's reports. We in the Egyptian subsection accepted Benny Kain's conclusions and began searching for more indications that the Egyptians were indeed planning a canal crossing with a large force. The only differences of opinion were over the timing. In the years preceding the Yom Kippur War, we made various predictions on when a crossing would take place. These prognoses were written on one of the walls in the subsection, and each "prophet" signed his name. The wags in the outfit say that the reason for widening the main street in the Kirya [IDF headquarters in Tel Aviv] and then the razing the historical building of Section 1 [originally the home of the religious leader of the Templers, a nineteenth century German millennial sect] was to erase every vestige that there were those in the Kirya who believed that war was coming.

The second discovery: preparing underwater passages for crossing the sweet water canal

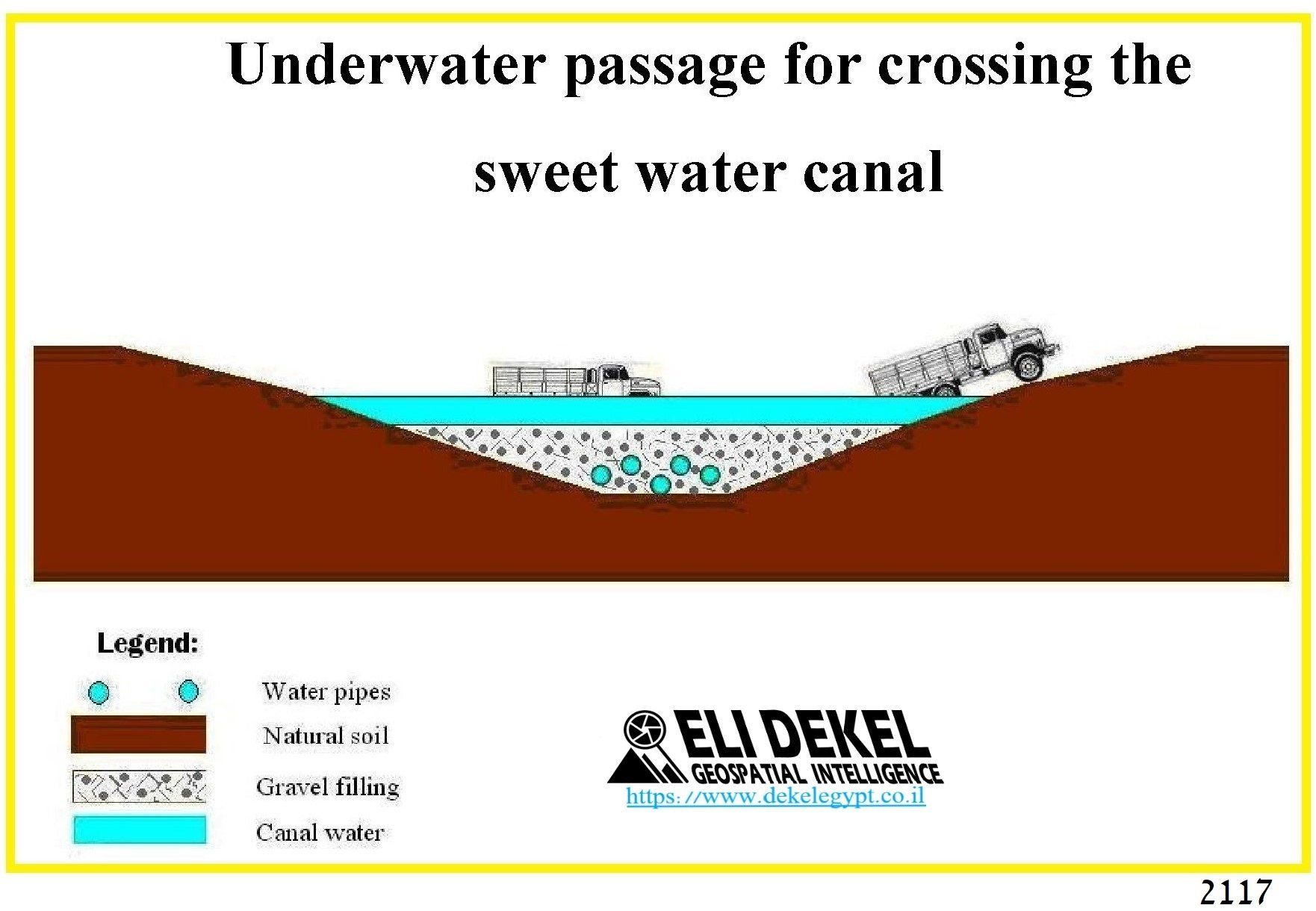

Shortly after the discovery of the road network and the bridge at the sweet water canal in the Deversoir area, more bridges were found in other sectors and it became clear (at least to the researchers in Section 1) that this indicated a comprehensive plan originating from the Egyptian chief of staff and not the just the whim of a local commander. While the bridges were still undergoing construction, Benny discovered other places where roads were being paved in the direction of the sweet water canal but no bridge being built across it.

At first glance it seemed that the bridge parts had not arrived, but when the delay extended to a longer period Benny was able to discern that a new type of bridge had been established, a device that he termed "the underwater passage." Pipes were laid on the canal bottom to allow for a continuous flow of water, then the infrastructure was covered with dirt and stones and the upper section of the "bridge" immersed underwater. A vehicle could easily cross the water obstacle.

At first this discovery elicited antagonism in the command, but Benny, in his systematic way, proved that construction material that had not been there earlier, had been stockpiled at the bridge sites and then "disappeared." This meant they had been thrown into the sweet water canal to serve as building components of an underwater passage. In the final analysis, Southern Command "bought" the underwater passages discovery, and the intelligence corridors began to absorb the fact that the Egyptian army was indeed creating an infrastructure designed for crossing the Suez Canal.

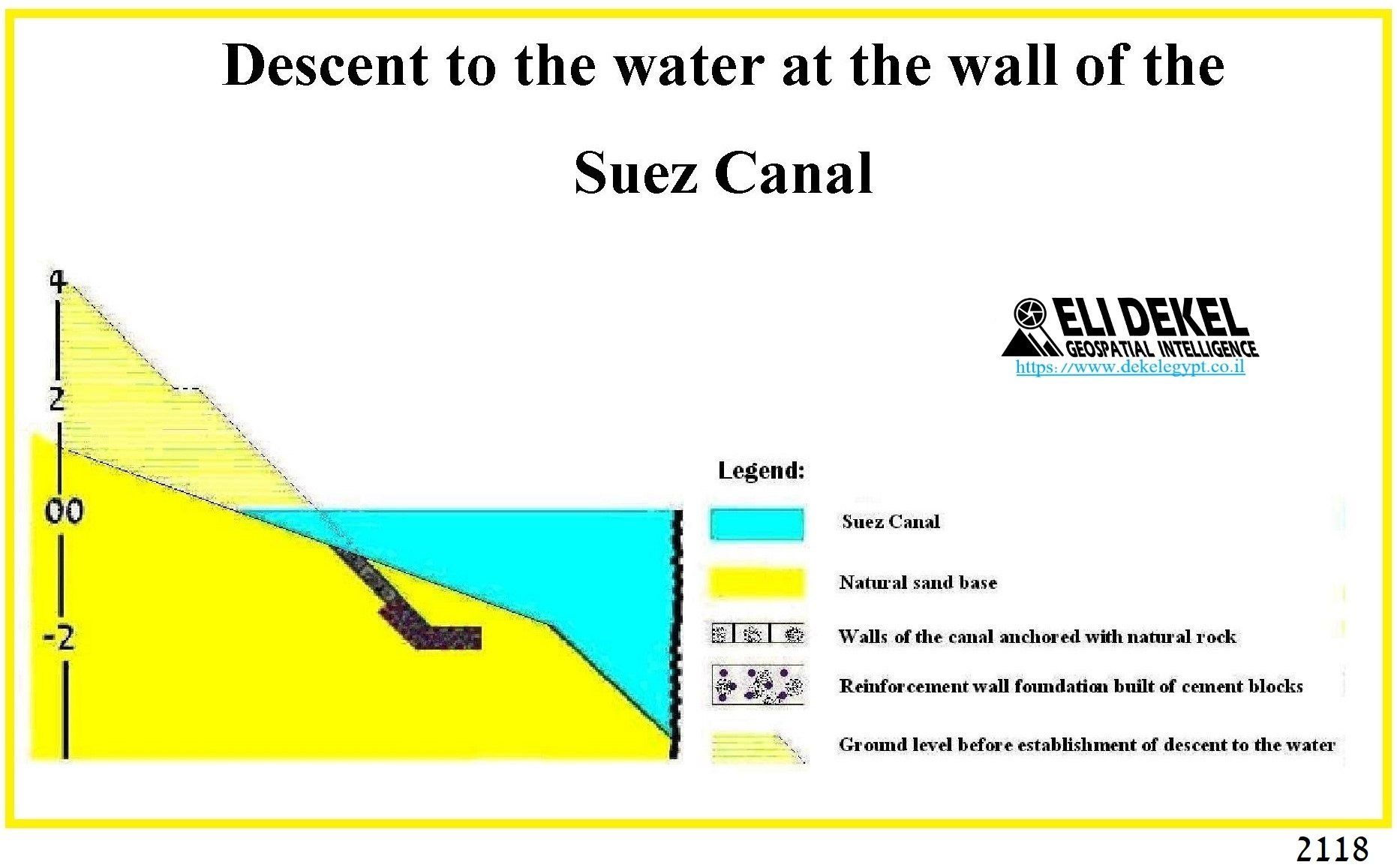

The third discovery: preparing the descent to the water and crossing platforms

After the Egyptians overcame the sweet water canal obstacle by means of bridges and underwater passages, they turned to the western bank of the Suez Canal. It will be remembered that the banks' cement and stone cubes, and especially its reinforcement wall, were obstacles for amphibious equipment. The Egyptians used bulldozers to break through the low dirt embankment and reinforcement wall in order to create an accessible descent to the amphibious equipment that would be dropped into the water. These breakthroughs - termed descents to the water - were

prepared openly, in the full light of day in front of our troops on the opposite bank. After the descents were completed, the Egyptians began leveling out platforms on the canal shore, each platform dozens of meters in length. We called them crossing platforms. Built between the descents to the water, the platforms would serve as assembly areas for bridge sections (from older bridging equipment) which would be thrown into the water once assembled. To the best of our knowledge, the descents were planned for infantry assault boats and for dropping the advanced, rapid-assembly, Russian-made PMP bridging equipment into the canal.

No one challenged the evidence and the implications of the construction work: a canal crossing was in the making. After the initial shock of the "brazen construction operations," which confirmed Benny Kain's conclusions, wore off, denial and counter-speculation came into play.

The new claim was: "Do you have any idea what an assault crossing entails? Just because bulldozer broke through a stone wall on the other side of the canal doesn’t mean that they Egyptians are planning a water obstacle crossing. Crossing the Suez Canal is an unbelievably complex operation that the Egyptians are incapable of."

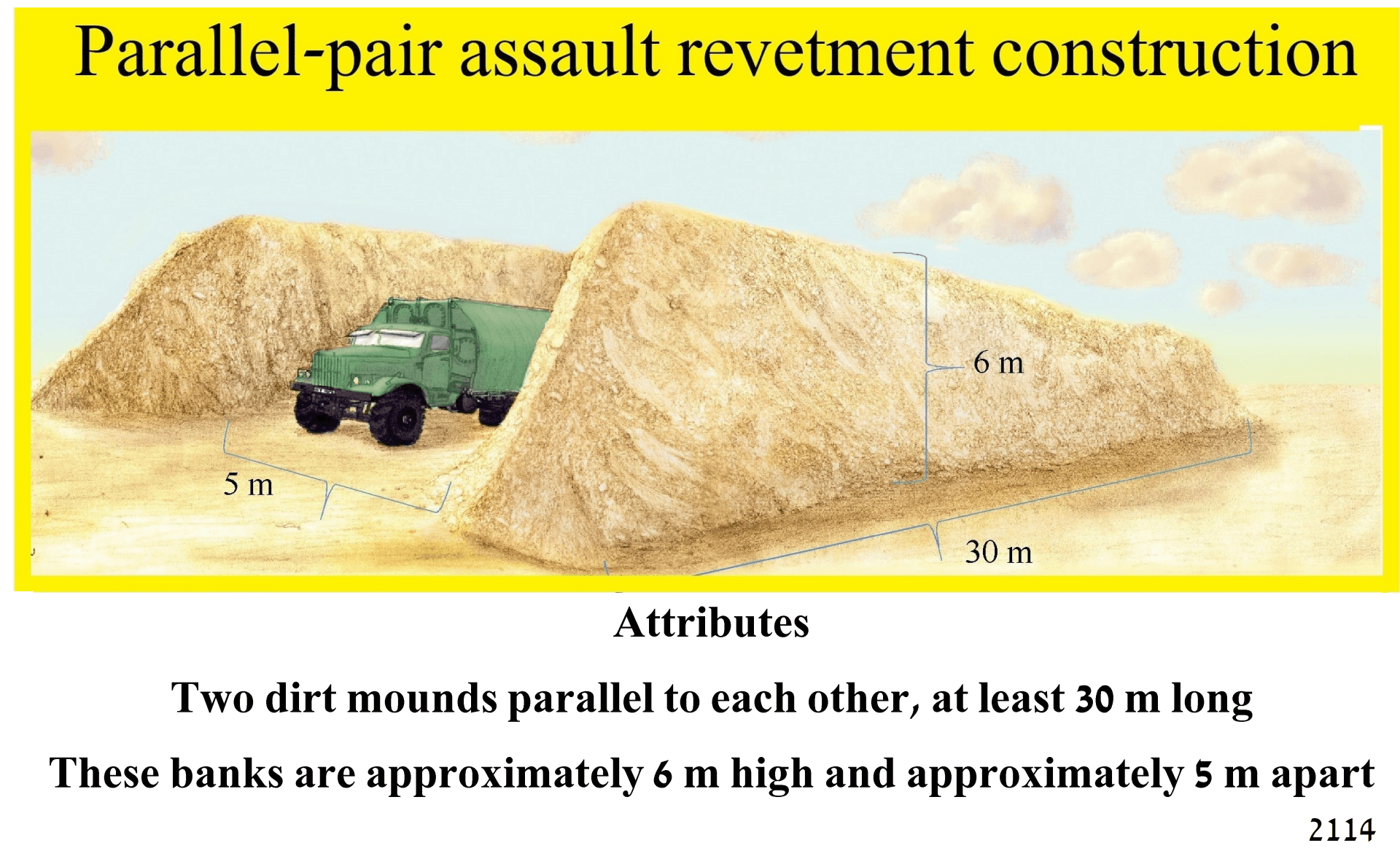

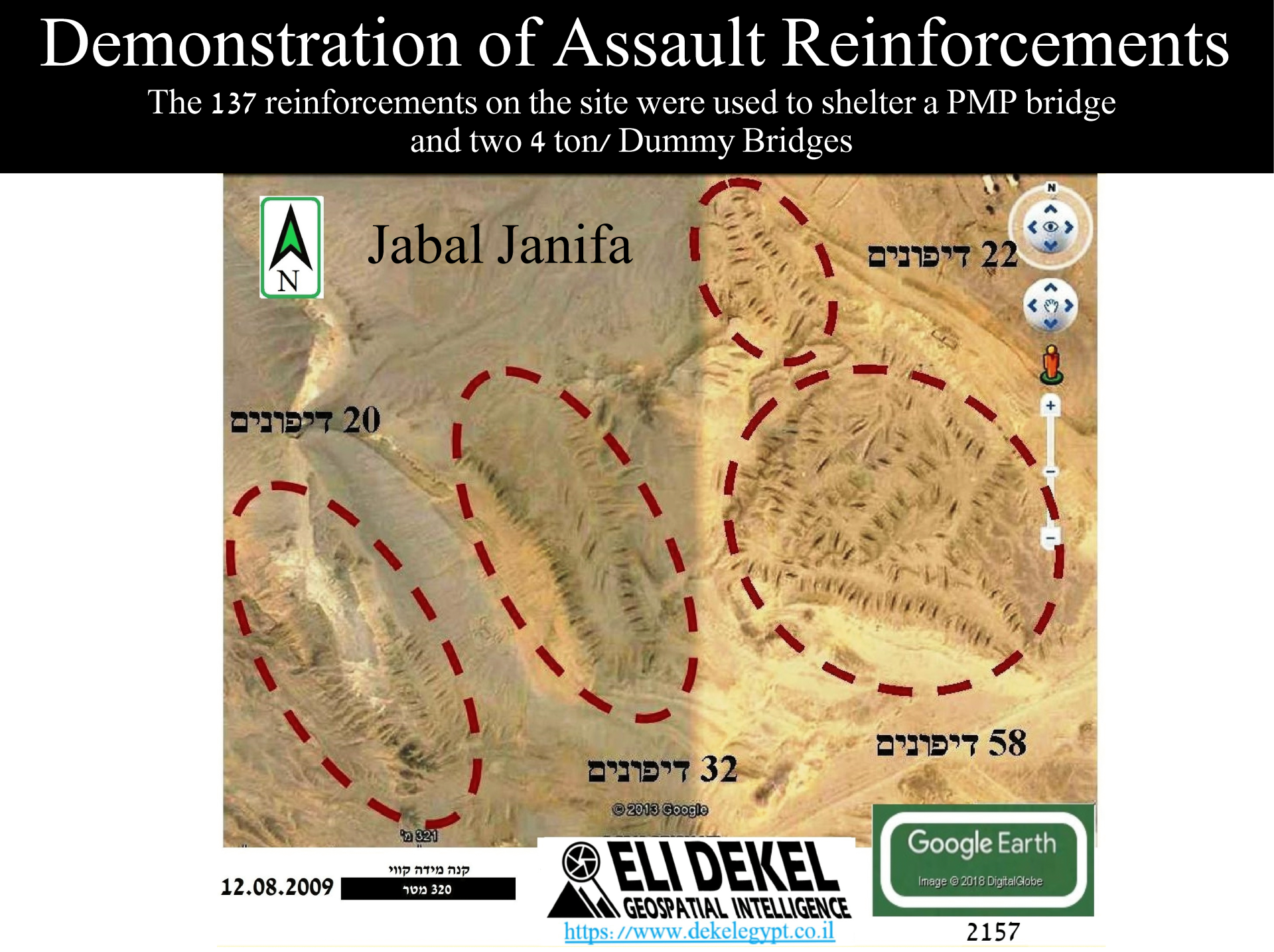

The fourth discovery: building "assault revetments" to protect the crossing equipment

Parallel to the descents to the water and the growing number of crossing platforms along the entire length of the canal, Benny now identified a new type of ground work being carried out five to ten kilometers west of the canal. Heavy mechanical equipment was building pairs of parallel dirt mounds separated by four meters. Each group numbered about thirty mounds, and the pairs were separated from the other at a distance of thirty to forty meters. Groups of these mounds began to appear along the canal in the Second and Third Army sectors.

Ground work of this type had never been seen before. It was obviously part of some kind of engineering enterprise, but its purpose was unclear. Benny lit upon the phenomenon and devoted a great deal of thought as to its intention. He came to the conclusion that the mounds were meant to serve as protective areas for the vehicles transporting the bridging and crossing equipment. But why?

During the War of Attrition the Israeli Air Force (IAF) carried out thousands of sorties. This made the protection of vehicles and armored fighting vehicles (AFVs) with "revetments" absolutely necessary for Egyptian units stationed even hundreds of kilometers from the contact line on the canal. The problem was that the shelters for the vehicles and AFVs that we had observed until then were three-sided elevated dirt embankments protecting the vehicles on at least three directions. The new system had a drawback: a vehicle entering or exiting the dug-out had to drive in reverse and by doing could jam the traffic and cause an accident. Benny came up with the original idea that the new revetment system was designed for rapid entry and egress from the revetment even at the cost of safety and protection of the equipment. He termed the new constructions "entry and exit revetments" and "assault revetments." He explained that the huge amount of bridging equipment, on which the entire crossing operation depended, consisted of hundreds of trucks loaded with bridging sections and various types of fording parts. The vehicles would be exposed to attack and had to be protected for hours until the equipment was dropped into the water and bridging operations commenced.

After discovering the assault revetments and realizing that the Egyptian army was working toward a large-scale crossing operation, it was decided to circulate a departmental intelligence review. The first idea was to publish a review that summarized the general aspects of the crossing,[3] but the Egyptian and technical sections "dragged their feet" and evaded coming forth with their input, explaining that they didn’t have the time to summarize the situation and put it down in writing. Since Section 1 was unwilling to wait any longer, the research department and "Jimka," the head of Section 1, decided that the survey would deal only with the ground aspect of the crossing, and that the rest of the intelligence corps would contribute their information on the other aspects at later date. In November 1971 a departmental intelligence review was published entitled "Ground Preparations for the Canal Crossing." Its bottom line was that the Egyptian army was preparing for a large-scale crossing along the entire length of the Suez Canal and was protecting the crossing equipment in order to limit possible damage to it and the crossing forces.

The review's publication forced the research department to examine the crossing evidence whose first signs, to recall, Benny Kain had already recognized in 1968, and that the military and technical sections were supposed to have studied. The military section completely ignored our revelations, brushing them aside with a wave of the hand. The Egyptian section and its military subsection, from the head of the section to the last of the research officers, adopted a policy of completely blackballing Section 1. For example, none of them visited the section or displayed any interest in its findings. The chasm between Section 1 and the rest of the intelligence research branches did not begin in 1970 nor did it end even after the self-righteous officers of Section 6 were given the boot following the Yom Kippur intelligence fiasco. One of the reasons for Section 6's disparagement of Section 1 may have been its access, at time informal, to sources of information that Section 1 was not privy to. This exclusivity may have bred a sense of superiority: "What right do you have to presume? We have the information from the 'horse's mouth,' which was another way of saying "you guys are on the sidelines." In addition to Section 1's exclusion from sources at the highest level, it was also barred in this period from attending all intelligence meetings held with the superpowers and foreign military intelligence services. What the directorate of the research department and the Section 6 staff did not realize in their cavalier ignorance was that the information that we deciphered in one air reconnaissance photo (if they knew how to decipher a recon photo correctly) was infinitely more valuable than any story obtained in meetings with secret agents or intelligence bodies. As a side note, I shall mention that while I was researching the subject of command and control (C2) in the Egyptian army I submitted a request, according to the instructions of the assistant department head of operations, Colonel Aharon Levran, to the military subsection to receive information on the subject. I was referred to an NCO, who offhandedly dew out a number of tattered card indices with meager information on C2. As to my query whether this was all they had, I was told that there were more urgent matters for them to deal with and I should be grateful that they were kind enough to talk to me. Praise the Lord who has endowed man with brains. Even without their help I managed to publish the review.

The technical section, on the other hand, dealt business-like with the crossing canal, stating that construction of floating bridges across the Suez Canal would take a rather long time. In practical terms this meant that the IDF had nothing to worry about: until the Egyptians succeeded in assembling pontoons and dropping them in the water so that their forces could move across them, the IDF would have time to mobilize its entire reserve layout. This reminds me of a curious episode. I took part in a discussion on a particular subject in the presence of the assistant head of the research department, Colonel Levran. A senior intelligence officer entered the room and the conversation between them focused on the crossing. The guest said something like: "I heard that the Egyptians are planning a crossing, but I don’t believe the nincompoops are capable of it. I pray that they'll be lured into giving it a try so we 'can stick it to 'em' and turn the Sinai peninsula into their graveyard." Aharon Levran was in complete agreement with the guest.

Benny Kain refused to "buy" the technical section's professional estimate of the time needed to assemble the bridges. He began pouring through the literature on the subject and studying material on water obstacle crossings in the Second World War. After an exhausting series of "battles" with the technical section's staff, Benny slowly convinced them to recalibrate their assessment of the time needed to put the bridges in place.

Needless to say, the Egyptian section and the technical group in the intelligence corps were not forthcoming in publishing their reviews to fill out the picture. Had they been more responsive, the surely would have noted that alongside the ground preparations, the Egyptian army was engaged in activity on an unprecedented scale, inter alia, in establishing three bridging brigades consisting of twenty-one battalions and innumerable engineering units to support the crossing operation, - from spearhead battalions to special assault battalions for laying pipelines for drinking water. All this, in addition to setting up an intensive training layout at all levels of the Egyptian army.

Finally, in early 1973, the technical section published a departmental survey on the crossing, its sectors, and the time required for setting up bridges. The survey hardly mentioned the Egyptian war machine that had been built to train the forces for carrying out the assignment.

The fifth discovery: assault revetments for crossing equipment being constructed in the field armies' rear

After the ceasefire that went into effect in August 1970, the IDF halted its aerial reconnaissance missions which had been penetrating Egyptian airspace. Now the aerial photographs of the Egyptian army between Cairo and the canal were taken at an oblique angle when the aircraft was over Israeli-occupied Sinai.

Naturally, the units deployed close to the Suez Canal "were sharply photographed" but further to the west and rear of the field armies on the Rubeiki-Tel el Kabir line (about 70 kilometers west of the canal) the photos became blurrier and trickier to decipher. These difficulties aside, Benny managed to discern in the distant area concentrations of assault revetments, 120-150 of them in each concentration. He figured that they were meant to serve as "entry platforms" for the crossing units before moving into the combat zone, the idea being that engineering units would pull the bridging equipment out of the storehouses, probably in Wadi Hof[4] south of Cairo, and deploy it in the entry platforms to the rear of the field armies until the order came to commence crossing operations. Or, the crossing units would advance to the assault revetments in the deployment areas on the canal front where they would wait for their turn to enter the water and/or assemble on the crossing platforms on the canal shore.

The collection layout, by the way, did not supply us with any information on where the huge stockpiles of crossing equipment were located. After the war, we read that the IDF collection layout did have intelligence sources, so it seems strange to me that no answer was forthcoming as to where the Egyptian army was storing its crossing equipment. I surmised that it was hidden in caves in Wadi Hof since I knew of no other depots capable of housing so great an amount of equipment, not even in the crossing school that I knew was located on the banks of the Nile at the foot of the caves. Documents captured during the Yom Kippur War confirmed my assumptions.

Benny's discovery was greeted with skepticism by the decipherers who examined the evidence. They argued that the oblique reconnaissance photos that Benny based his discovery on could not be interpreted as assault revetments and there was no way their number could be determined. Benny stuck to his assessment and received "Jimka's" backing.

To this day I don’t know if the Egyptians actually used the revetments on the entry platforms in the Yom Kippur War or, in an act of deception, they leapfrogged the "intermediate stage" in the armies' rear and deployed for the crossing from the assault revetments near the canal. Air reconnaissance photos taken during the war very clearly showed the assault revetments in the rear of the armies, so that the skeptics again had to admit that Benny was the master decipherer.

Additional steps identified as Egyptian war preparations

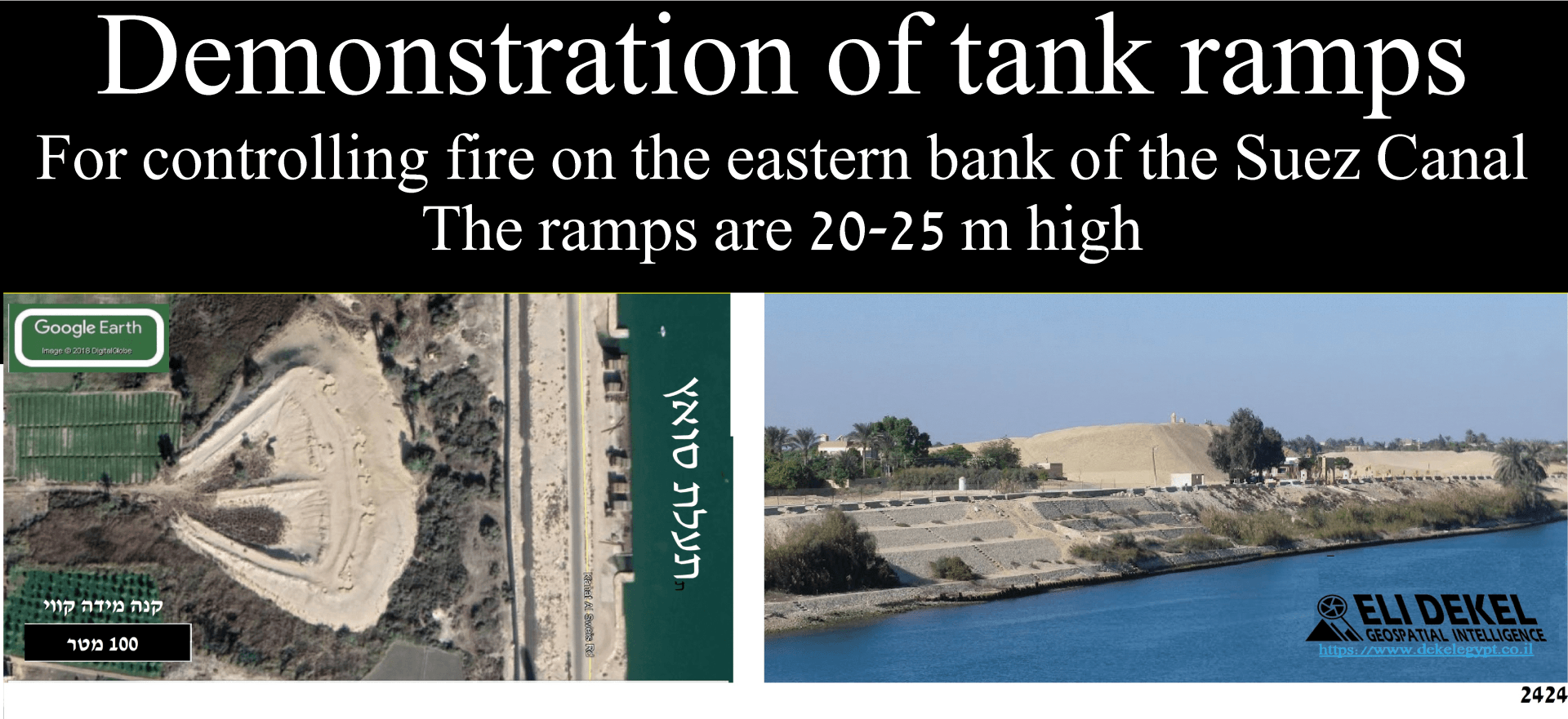

Building the tank ramps

In mid-1972, as preparations for the canal crossing were in full swing – the descent to the water, the crossing platforms, and assault revetments – the Egyptians began raising the dirt embankments to a height of 20-25 meters, higher than the embankments on the Bar-Lev Line. These elevations were made on the western bank of the canal, each elevation scores of meters in length. Southern Command intelligence interpreted them as positions for Egyptian spotters and tank hunter teams equipped with Sagger missiles if the War of Attrition reignited. Benny claimed that the embankments were intended for tanks

to provide suppressive fire for the crossing units. Benny's analysis piqued the chief intelligence officer of Southern Command, Lieutenant Colonel Yehoshua Saguy, who sent off an angry letter demanding that Section 1 stay out of matters that didn’t concern it: the inclines precluded the ascent of tanks, and even if a tank did drive up – it would be knocked down before it could get off the first round. Despite this "erudite" response of the Southern Command's intelligence officer, Benny obstinately stuck to his view, and all of our publications dealing with the ramps supported his interpretation.

Constructing command and control (C2) strongholds

C2 in the Egyptian army and C2 strongholds on the Suez Canal front in particular is a complex subject that requires a separate study. In the context of the crossing I'll mention only the following points:

According to the Soviet doctrine, every unit at the brigade level and above should strive to attain the following command posts:

A. A rear command post serving the formations' manpower and personnel administration and supply layouts (in the Egyptian army this was termed "the head of administrative affairs").

B. A main command post serving the formation's commander, and after him all of the general staff elements: intelligence, signal corps, artillery, and so forth. The formation operates in this command post only in peacetime.

C. An alternative command post that serves the commander and his staff in wartime. This assumes that the enemy will locate the main command post serving the formation in peacetime so that an effort should be made to transfer C2 to a prearranged alternative command post

just prior to 'H' hour.

D. A forward command post serving the commander and a small team of staff officers for observation and control of the battlefield.

This being the situation, the alternative command post and forward command post would appear empty all year, which precluded our locating them by eavesdropping. Even detecting them in air reconnaissance photos was a tricky task. Benny did his work thoroughly and found a large number of the command posts that could serve the Egyptians during the canal crossing. It should be stressed that all of our discoveries were made without any help from the intelligence corps units involved in this subject. The reason for the refusal to help stemmed, in my opinion, mainly from jealousy in the guise of safeguarding the security of the sources. After the war, when captured maps and documents began to flow in, and after we scoured the recently captured areas on the western bank, we witnessed with our own eyes how right Benny had been and the enormity of his task in successfully identifying the camouflaged command posts and mock facilities. The subject of C2 was published before the war in a special intelligence survey so that the rest of intelligence corps and general staff/operations could gain an impression, if they cared to, that the Egyptian army takes its war preparations seriously and devotes enormous resources toward that goal.

The establishment of an assault layout for supplying drinking water

Even though Egypt sits on vast water sources, the water has to go through purification installations to make it potable. In all the cities along the Suez Canal, water facilities have supplied drinking water to a population of over a million people from time immemorial. The Egyptian units deployed along the length of the canal after the Six-Day War debacle received their water from these facilities. Drinking water was supplied to units deployed in the area by tankers and in jerrycans. As long as the army was engaged in active defense and training, the water supply could be based on tankers, but once an operational plan for crossing the canal began to unfold, the Egyptian planners had to solve the problem of water supply to the crossing forces since the great number of tankers needed, if they joined the heavy traffic on the bridges, could hinder the crossing. The solution was to lay a special water pipe along the western canal road, and establish water reservoirs and pumping stations to answer the needs of the crossing force. Section 1's Egyptian subsection, with the assistance of a water expert from the reserves, studied the matter and circulated an intelligence review. Its message: the new water system was designed to serve the Egyptian army in case of a renewal of fighting on the canal (this was after the ceasefire went into effect in August 1970) or in the event of a canal crossing.[5]

We learned during the Yom Kippur War that the Egyptians had established special engineering assault battalions for the rapid deployment of the water pipes. The battalions linked the pipes to the reservoirs that had been built to the west and pumped the water in aluminum pipes (similar to the water pipes used in Israeli agricultural fields) to Sinai. Water reservoirs made of rubberized tarpaulin (a strong, water resistant canvas) were set up along the length of the pipe. To the best of my knowledge, we had no inkling of these engineering assault battalions before the war.

Training for the crossing

The complex military operation of crossing the Suez Canal required five infantry divisions assisted by dozens of armor, artillery, antitank, signal corps, and other units. Naturally such a force had to undergo basic training:

• Training engineering units to use complex equipment in various capacities (assembling different types of bridges, breaking through the embankment on the Bar-Lev Line, laying water pipes).

• Training the forces in the advance towards the bridges, in crossing them in special combat groups, seizing control of the eastern bank, and deploying for the expected counterattack.

Engineering training included movement to the crossing sector, bridge construction, and laying down the rest of the fording equipment. The engineering layout included two brigade formations, one for each army, as well as a general staff reserve brigade designated to reinforce the crossing and serve as a reserve deep in the rear of Egypt for building floating bridges in case the IAF knocked out the permanent bridges on the Nile.

Each brigade consisted of five bridging battalions for different types of bridges and two support battalions for transportation and special equipment. A very large number of engineering units indirectly lent their support during the actual crossing, in addition to the divisions' organic engineering units. The Egyptian corps of engineers established a sophisticated training base in the Helwan region south of Cairo where the engineering units underwent bridging exercises where the Nile was similar to the Suez Canal. The engineering forces had two other training areas: Lake Fayum, where amphibious landing craft exercises were held in an area similar to the Bitter Lakes of the Suez Canal; and the island of el Balah in the Suez Canal. This island had been created during the excavation of the Suez Canal and its purpose was to enable the two-way passage of ships through the canal. After the Six-Day War the island remained in Egyptian hands and was the only spot along the entire length of the canal where the Egyptians controlled both

banks (they also controlled the two banks at Port Said in the northern exit of the canal, but the city was surrounded by muddy lakes unfit for crossing exercises). On el Balah Island, directly in front of the Israeli

lookout posts, the Egyptians held a series of exercises for breaking through the Bar-Lev embankment by using water hoses based on high-powered pumps that had been procured specifically for this purpose.

The crossing operation also required training the forces in the advance to the bridges, fording water obstacles (the fresh water canal and Suez Canal), penetrating the Bar-Lev Line, capturing the strongholds, gaining control of the eastern bank, and deploying defensively for the counterattack. All this training was held in two areas:

• A sophisticated training facility set up in the Hataba region in the Western Desert. The Nile (Rosetta branch) was similar to the Suez Canal and the Ibrahimi Canal that flowed parallel to the Nile resembled the sweet water canal. One brigade after another underwent training in Hataba where they practiced desert operational movement, fording the Suez Canal, and storming and securing the Bar-Lev Line.

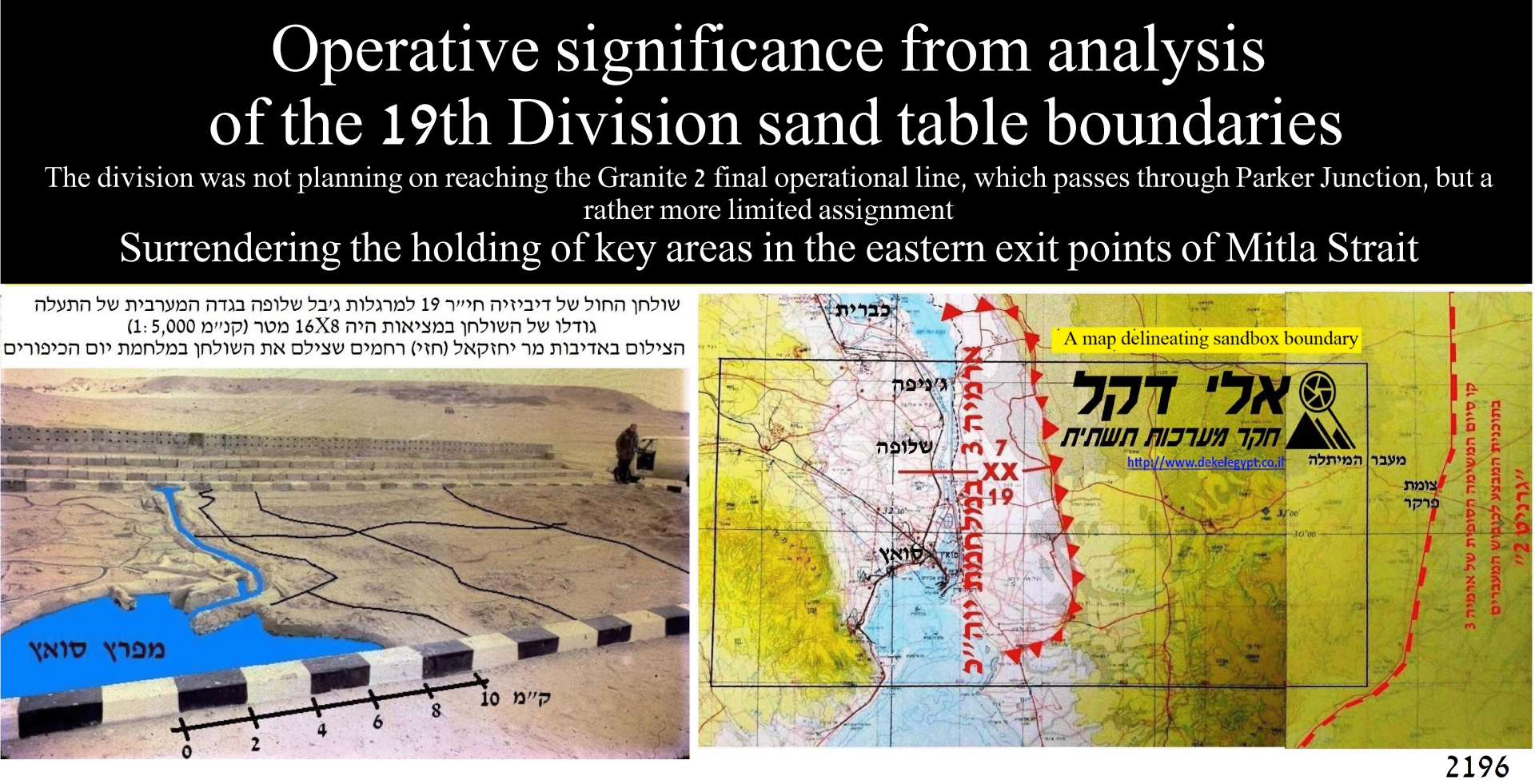

• Dry-run divisional and corps (army) training exercises were held in the Qumatia region. These exercises (in a north-to-south movement) were carried out along the Cairo-Suez railway which resembled the sweet water canal obstacle. The road to the astronomical observatory in Qutamia was used to simulate the fighting in the Gidi and Mitle mountain corridors.

In addition to these training areas, a sophisticated sand table[6] was built in every battalion deployment area which depicted the battalion sector and its missions on the eastern bank.

The debate over Egyptian readiness for a canal crossing

Approximately three months before the war, the head of Section 1, Lieutenant Colonel Zvika Shiller, called a meeting in his office to discuss "if the Egyptian army has completed ground preparations for a canal crossing." In other words, was the Egyptian army ready, from an engineering point of view, to cross the Suez Canal, and if not, when? All of the officers and NCOs in the subsection were invited, even those like me who didn’t deal with the subject of the crossing. Also invited were: Major (res.) Benny Kain; Major Yaakov ("Yankil") Rosenfeld – representing Section 6; and Major Noam Shapira – representing Unit 8200 (SIGINT).

It was quite unusual for the head of Section 1 to invite "outsiders" to a discussion on matters not directly connected to IDF operations, especially as the ceasefire was in effect at the time and no one took much interest in us or our research. Even more surprising was that a representative of Section 6 attended. During the eleven years that I served in the section never once did I witness the head of the Egyptian section, or the head of the military subsection, or any of their staff cross the threshold of the Egyptian subsection in Section 1.

The reason that Zvika convened the meeting was that the Egyptians had begun building dirt embankments along the access roads leading to the Suez Canal. We assumed that their purpose was to prevent our forces from observing movement on the roads. The construction work had begun in the Genifa sector south of Little Bitter Lake after several months of quiet during which the Egyptians had made no improvements in ground preparations at the canal.

The meeting started off with a brief survey of the Egyptians' ground preparations for a crossing. The subject was presented by Captain Avi Himmelblau who, at the time, was a civilian employed part time by the army and who was responsible for the canal front in Section 1's Egyptian subsection. After Himmelblau's review, the head of the section opened the discussion with the question: Can we say that the Egyptian army has completed its ground preparations for a crossing or does the latest building of concealment embankments point to the beginning of a process that will spread to the rest of the crossing sectors.

Yankil, Section 6's representative, said that he would relate only to the issue of ground preparations and that he had no intention of expanding the discussion to include the Egyptian army's readiness for war. But since the Egyptians lacked "things" in many areas that he preferred not to go into detail about, then, in his opinion the Egyptians had all the time in the world to complete the dirt embankment project and expand it along the entire canal front.

Avi Himmelblau believed that the embankment project would eventually extend to all of the crossing sectors, including the Second Army's where ground works had not begun yet, so that we can "sleep quietly" for a few months, maybe even half a year. I said that the Egyptian army had basically completed ground preparations for the crossing and the Egyptian engineering corps commander could report to the chief of staff "Everything is ready, sir!" The question of concealment embankments, I explained, is like wallpaper covering on the walls of a new house: "It's attractive, but unnecessary." It is natural that everyone wants to make improvements, but it is definitely not a prerequisite for a crossing operation. Benny Kain supported my assessment. To the best of my recollection and that of the other participants in the discussion whom I spoke with while writing this article, Zvika neither summed up the meeting nor published an executive summary. In August 1973 a Section 1 executive summary on the subject of a canal crossing was circulated in the research department prior to the annual situational assessment discussion. The paper stated that ground preparations had been completed in the Second Army's crossing sector, but Third Army sectors were still incomplete and that additional work would probably be carried out. In retrospect, it seems strange that this discussion was not held with the attendance of the head of the research department, Brigadier General Arye Shalev.

The Egyptian home front's war preparations

In addition to the Egyptian army's ground preparations for the canal crossing, the Egyptian homefront, too, prepared for the coming war. These preparations included amassing emergency stockpiles and protecting strategic facilities from an IDF attack, especially by the IAF. I was responsible for tracking the changes being made in Egypt's depth.[7]

During the 1968-1971 War of Attrition when Egypt was pounded by Israeli air strikes, it began setting up defense layouts at strategic targets - protective walls and heavily strengthened bunkers at oil reservoirs, electrical transformers, and so forth.

The following steps were taken to protect the homefront from an attack:

A. Building at least ten enormous oil storage depots, most of them underground and well-camouflaged. Reservoirs for the civilian population were constructed in the Delta and Nile Valley.

B. The bridges and dams on the Nile were of paramount importance. The Egyptians covered them with protective nets (during the War of Attrition the IAF tried to hit the Isna Dam in the south of Egypt with a torpedo-like bomb). Barrage balloon units were also deployed at the bridges against low flying aircraft.

C. Access roads were paved and jetties were built near the Nile's important bridges. This infrastructure was designed to enable floating bridges to be thrown across the Nile in case the regular bridges were put out of commission. For example, in the village of e-Ziat in the northwestern part of the Delta, jetties were constructed and access roads paved. The Egyptian corps of engineers held a bridging and crossing brigade in reserve (in addition to two bridging brigades that were attached to the field armies). The reserve brigade was probably designated, inter alia, for bridge construction in Egypt's depth.

The Egyptians invested great sums in building sophisticated mock facilities (deception tactics). We knew about this from the Six-Day War[8] but the effort was now accelerated at every level, from fake surface-to-air missile bases to phony C2 strongholds at the highest level of Egyptian command. Five months before the Yom Kippur War I discovered that the Egyptians had covered their vital facilities in Cairo with camouflage paint, and our report emphasized that this was the first time the Egyptians had done this. A draft of the report linked the camouflage paint to the war preparations. The head office of the research department excised the war-oriented paragraph and substituted something far more tepid. Close to the outbreak of the Yom Kippur War, the Egyptians went one step further than just camouflage paint (had they read our review?) when they built a fake facility next to the general staff command stronghold.

Preparations for the canal crossing on the eve of the Yom Kippur War

In early October 1973 the Egyptian army declared a state of alert under the guise of a combined-forces exercise. Our intelligence layout also went on alert and began tracking Egyptian military activity. The weather prevented photo reconnaissance flights so the only incoming information was from eavesdropping sources and observation by our forces. The latter reported construction going on that was enhancing the descents to the water. On October 2 we circulated an intelligence report on irregular activity in the Third Army sector for improving the descents to the water.

On Thursday, October 4 the long-awaited air reconnaissance sortie was finally carried out. In this period the film was developed on a positive celluloid roll and, by means of an MIM4[9] deciphering device, was scanned and interpreted. Generally the film was sent to the deciphering unit to perform a quick scan (immediate interpretation) to identify enemy military units, but given the critical nature of the situation, this time the deciphering unit made a more systematic appraisal of the photo. Thus, we in Section 1 who dealt with the ground infrastructure received the film late that night. Avi Himmelblau worked on it. Avi found large-scale activity in improving the descents to the water. He also noted that the sandbags blocking the descents had been removed, and he discovered, for the first time in the canal theater, that transport vehicles with crossing equipment had taken cover in the assault revetments. Until this discovery, the real purpose of the revetments as hideaways for crossing equipment had only been conjecture.

In the predawn hours, after completing his work, Avi wrote a long report on a teleprinter (standard operating procedure) summing up the new sightings in the area. He underscored that improvement encompassed nearly 80% of the descents to the water. In the morning, when the section head arrived, Lieutenant Colonel Zvika Shiller, it was decided to immediately publish an intelligence report. Before this, however, the reconnaissance photo was reexamined, and this time it turned out that only 50% of descents had actually undergone improvement. The report mentioned that the sandbag removal from the descents was indeed an irregular occurrence. The head of the Egyptian subsection, Major Dov Adler, claims the draft of the report included a paragraph stating that this type of activity on such a wide-scale could mean only one thing – war. I do not have a draft of the report and cannot confirm or refute his claim.

The intelligence review went through editing and verification by the head office of the research department. Reports in Section 1's field of work were usually sent for confirmation to the head of the operations research department, Colonel Aharon Levran. When Levran received a draft of the report, he contacted Section 1 and said that he had already reported to the chief of staff that 80% of the descents to the water had undergone enhancement and now he reads that only 50% had been improved. Zvika was seething and sharply rebuked the heads of the Egyptian subsection Dov Adler and Avi Himmelblau for giving a bad name to Section 1 as a unit whose reports are unreliable. He ordered them to recheck their findings. A careful recheck showed that Avi's initial reporting had been in error. After being duly revised, the report was finally published.

When the printed report reached the section, we noticed that an explanatory paragraph had been added to the effect that the preparations were part of a combined-forces exercise. On the other hand, our part of the review that linked this intensified large-scale activity with war was entirely expunged. We didn’t put up a fight, and didn’t appeal the changes that had been introduced[10], perhaps because case, the following day, Saturday, October 6, the we were worn out from Zvika's and Levran's reprimands. Whatever the Egyptians launched the Yom Kippur War and crossed the Suez Canal with five infantry divisions according to the model that we had built and had been tracking since 1968.

Conclusion

In 1980, Sa'ad al-din Shazli, the Egyptian chief of staff in the Yom Kippur War, published his book Crossing the Canal.[11] According to Shazli: ". . . The planning of the 1973 attack began already in 1968, and predated to a considerable degree our operational capability. Over the next four years our strength continued to increase and our plans grew more realistic. The gap between the plan and [our] ability which had been enormous in 1968 narrowed from year to year and from exercise to exercise until October 1973 when the military exercise became reality, and the plans and abilities a single entity.

Elsewhere he avows: ". . . one principle that we never had in doubt, even during the reassessment, was that we would have to cross the canal on as wide a front as possible. This principle was the cornerstone of our thinking already in 1968. [My emphasis – E.D.]

Identifying the Egyptian army's preparations for crossing the Suez Canal began in 1968. Tracking and analyzing the Egyptian military operation during the crossing are sterling examples of the field research that exceeded the rest of the elements in intelligence corps. In this study, the human factor stands out as the key tool in intelligence research. I am referring to information gathering and deciphering, the need for original thinking, and the ceaseless struggle to fight for your assessments despite the occasional hostility of group dynamics.

Epilogue – Additions to the Essay included in the Book

The above essay has been translated from my book Modiin Talush Me’H a’Karka (Groundless Intelligence – Success and Failure in the IDF’s Geographic Military Intelligence). The essay primarily documents the information we, at the IDF’s spatial research branch of the intelligence division’s research arm, had in our possession on the Egyptian crossing prior to the Yom Kippur war. Following publication of the book in 2010, I continued studying the subject, and using recovered documents and additional materials have obtained additional figures supplementing those included in the essay, which are included below and aid in understanding the Egyptian crossing operation:

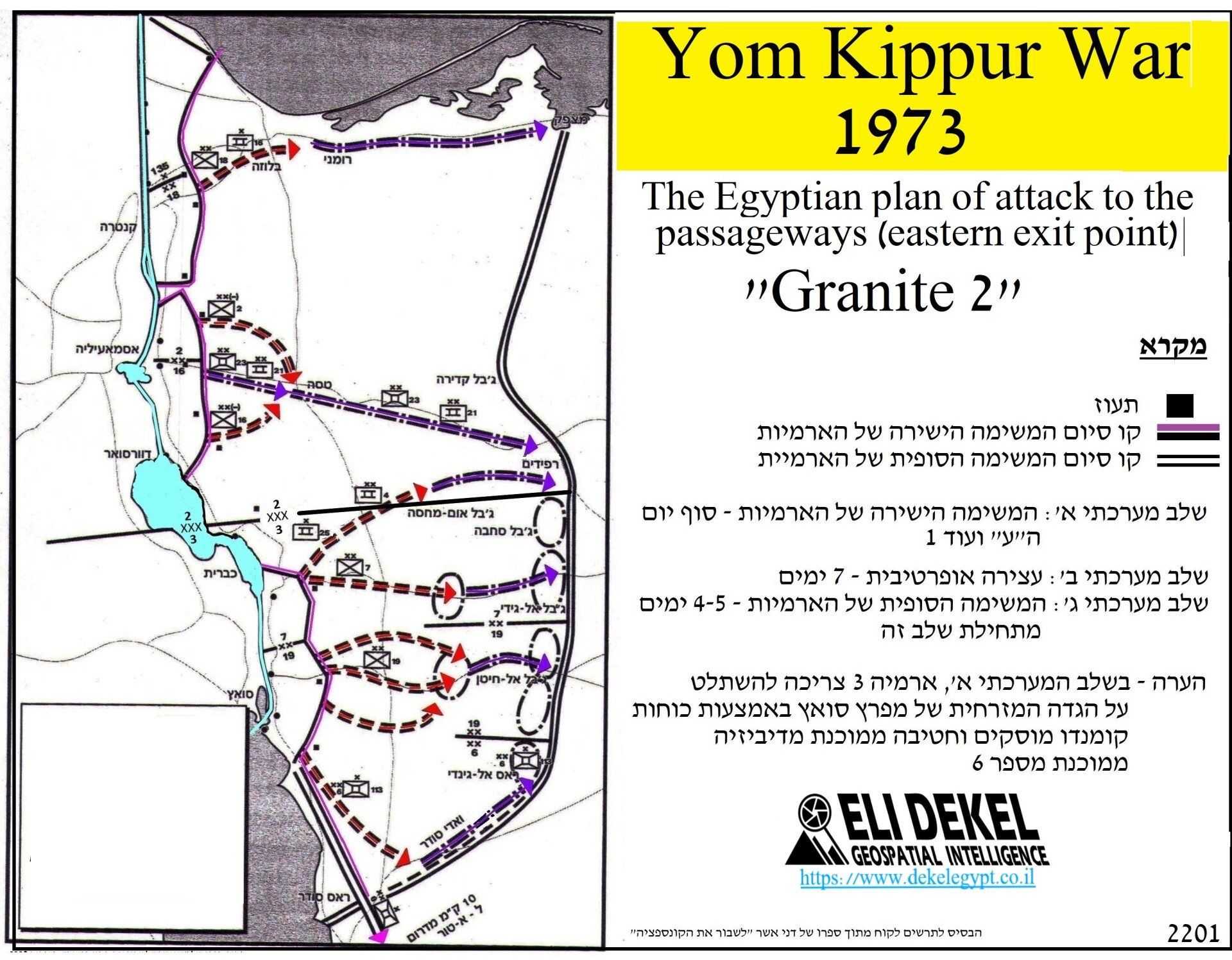

The Egyptian War Plan – Granite 2

The Egyptian Granite 2 war plan, which dictated the forces crossing the Canal march to the line of border-crossings (Refidim, Gidi and Mitla Passes) was known to the intelligence arm prior to the war and made public by it, with the Operation Map being published in many books. In my opinion, the border between the 2nd and 3rd Armies, in all publications I am familiar with, is incorrect! Therefore, following is the Operation Map as amended by me. In this map, the 25th Independent Armor Division and the 4th Armored Division, which were subordinate to the 3rd Army, become subordinate to the 2nd Army after crossing the canal and arriving at Refidim Pass.

In actuality, the Egyptians abandon this plan in 1972 and switch to a more limited scheme codenamed High Minarets [13]. The new plan was known only to a very few in the top echelon of the Egyptian army. The IDF’s intelligence arm was unfamiliar with the plan, and erroneously thought the Egyptians were sticking with Granite 2.

Scope of the Work to Construct the Assault Reinforcements

The myriad crossing equipment possessed by the Egyptians necessitated earthwork encompassing approximately 5,000,000 m². The table below details the calculation used to arrive at this figure

Methods for Penetrating the Bar-Lev Defenses

Shortly after the Six Day War, the Egyptians initiated the War of Attrition, in which they targeted IDF forces stationed along the canal using massive artillery bombardments from the wide range of artillery equipment possessed by the Egyptians. In response, the IDF established the Bar-Lev Line, which consisted of 30 military posts and a dirt embankment to protect the forces moving between the posts. With the end of the War of Attrition, in August, 1970, the IDF enhanced the Bar-Lev defenses by reconstructing the posts with superior reinforcements and by raising the height of the embankment to between 15 and 20 m. A higher embankment created an impenetrable obstacle for any Egyptian planner. In order to breach this obstacle, the Egyptians experimented with a number of methods, finally settling on dissipating the dirt embankment using water pumps ordinarily used for firefighting. Such equipment is pictured in the photographs below.

Actual Egyptian Crossing Force by Divisional Sector

The diagram below, based on retrieved operational orders documents, shows the crossing force in the 7th Infantry Brigade’s sector. The division in this sector was allocated two “heavy” bridges which allow for tank movement. I estimate that the crossing equipment allocated to the 2nd and 16th Divisions crossing sectors were similar to those in the diagram below. In contrast, in the southern crossing sector (most certainly the 18th Division) and the northern sector (possibly the 18th Division), the divisions were allocated only one heavy bridge. The second bridge was an LPP bridge capable of handling no more than 25 tons – i.e., suitable for all military equipment save for ta

Orders of Battle and Preparations of the 3rd Army’s Bridging Division

An analysis of retrieved documents finds that the bridging units began preparations at the further end of the canal by September 25, 1973, i.e., 12 days before the war. To the best of my knowledge, the intelligence branch was only made aware of the crossing units’ arrival two or three days before the war. From the deployment maps below, we find that the forces arriving in the assembly areas on September 25, 1973, were positioned in a rear assault reinforcement network. Most of these units advanced to the front networks on October 3, 1973. An additional advance, prior to hitting the water, was conducted on October 6, 1973 (no map shows deployment on this date).

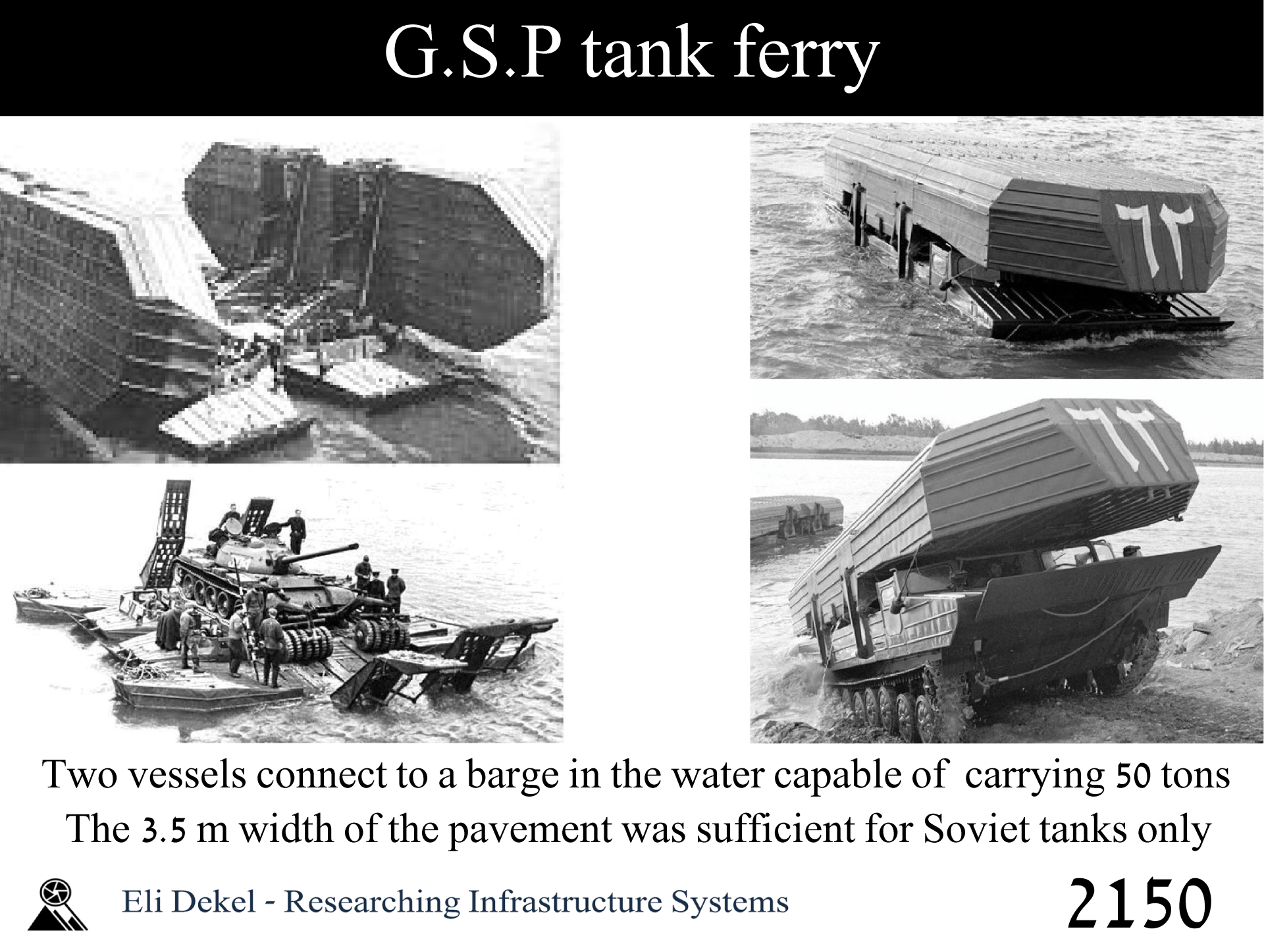

Mobile GSP Tank Ferry

A few months prior to the Yom Kippur War, the Egyptian army acquired mobile GSP Tank ferries. The intelligence branch was familiar with this type of ferry, but to the best of my knowledge was unaware the Egyptians were acquiring them. This equipment is in the possession of the Egyptian Order of Battle till today, October 2020.

Nots:

[1]. In February 1960 an Egyptian armor division crossed the Suez Canal and deployed close to the Egyptian-Israeli border. Israeli intelligence discovered it only after the Egyptian force was in position across from Israel's Nitzana region.

[2]. By a twist of fate the IDF crossed the canal in this area in the Yom Kippur War.

[3]. From Egyptian ground preparations (Section 1's responsibility) to the procurement of crossing equipment (responsibility of Section 7's technical section in the research department) and troop training and war readiness (Section 6's Egyptian subsection).

[4]. For thousands of years the caves of Wadi Hof have served the Egyptians: as a quarry for the pyramids and later as a source of building material in the construction of Cairo. In World War Two the British used caves as its main storerooms for war materiel. Access roads were paved and even a railway line for freight cars led to the caves. The Egyptians continued to improve the site and at one time even stored aircraft and tanks in them.

[5]. With the wisdom of hindsight, and after tracking the development of the military infrastructure in Sinai after the Yom Kippur War, it seems that given the establishment of the infrastructure for a water system and the absence of a parallel oil supply system, we could have derived the real reason for the layout and the Egyptians' aims in the Yom Kippur War. See the chapter "Mistakes in Field Research." In my book Groudless Intelligence.

[6]. Major Yoav Sharon, deciphering unit, did a superlative job in discovering that the sand tables.

[7]. Some of this we learned only after the war because of the lack of air reconnaissance photos and the rather flimsy interpretations in our possession, excluding information from other sources, but I did not devote enough effort in understanding it.

[8]. See the chapter "The Command Post in Rishat Lehman." In my book Groudless Intelligence.

[9]. The deciphering device is based on a light table on which the roll of film is moved by electrical motors. A stereoscope is positioned above the film and can be moved across the entire film area. The stereoscope provides a three dimensional view of photographs and enables magnification with a kind of microscope.

[10]. According to Uri Bar-Yosef's book The Lookout Fell Asleep (Zmora Bitan 2001), the head of the military subsection, Major Yaakov Rosenfeld ("Yankil") of the Egyptian section (Section 6), published a report based on the deciphered data from the same reconnaissance sortie summing the most recent developments in Egyptian deployment. Among other things: the Egyptian army has added three hundred additional artillery pieces to the 800 already in the sector this year; in each divisional sector one of the assault revetment concentrations appears to have crossing equipment; in one of the concentrations we spotted, with a high degree of probability, GSP amphibious ferries; and in most of the "courtyards" we located a tank platoon was found the foot of the tank ramps. The report was conveyed, as always, to the head office of the research department for approval. There they tried to "tone to down," but because of Yankil's refusal it was published as it was. This shows how stubbornness was sometimes needed to force the head office of research department to remove an interpretation that was unacceptable to the author of the report. How sad that Section I did not do the same.

[11]. Shazali, Sa'ad al-Din, Crossing the Canal (Tel Aviv, Ma'arachot Publishers, 1987). [Hebrew]